Source: Art Mag

Shahzia Sikander, like Deutsche Bank’s “Artist of the Year” 2013, Imran Qureshi, belongs to a generation of Pakistani artists who have radically renewed centuries-old miniature painting. Sikander, who is represented in the Deutsche Bank Collection, mixes traditional motifs with various cultural references and transfers her collages to different media, from wall painting to animation video. Cheryl Kaplan met with the artist, who recently received the „U.S. Department of State - Medal of Arts“ from Hillary Clinton, in New York for an exclusive interview.

Shahzia Sikander, like Deutsche Bank’s “Artist of the Year” 2013, Imran Qureshi, belongs to a generation of Pakistani artists who have radically renewed centuries-old miniature painting. Sikander, who is represented in the Deutsche Bank Collection, mixes traditional motifs with various cultural references and transfers her collages to different media, from wall painting to animation video. Cheryl Kaplan met with the artist, who recently received the „U.S. Department of State - Medal of Arts“ from Hillary Clinton, in New York for an exclusive interview.

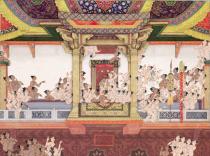

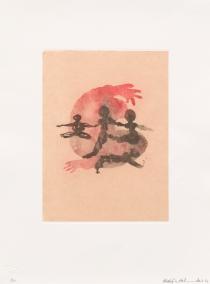

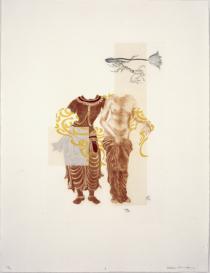

| In Shahzia Sikander’s Big Dog Series, headless robotic dogs, fashioned after U.S. military drones in Afghanistan, chase wildly through the legs of a Sumo wrestler. Lifting a cow with his bare hands, the wrestler looks back at a plump goddess wielding a megaphone. This trumped up version of a classic hunt or battle scene, so familiar to us from paintings by Rubens and Delacroix or Persian miniature painting, is just one example of how Sikander conjoins the often separate worlds of East and West. Her exquisitely rendered gouache drawings, paintings, animated films and projections are built in rich, luminous layers, a technique she first learned from miniature painting which she mastered at the National College of Art in Lahore, Pakistan. Also Imran Qureshi, Deutsche Bank’s “Artist of the Year” 2013, studied at the NCA. Sikander grew up during the oppressive military regime of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq in the 1970s and 1980s and speaks several languages, including Urdu, English, Punjabi and Arabic. Cataclysmic events are the lifeblood of Sikander’s visual language, and yet, there is great humor in her work. At times, her odd-ball use of allegory and vaudevillian drama turn history into a quixotic narrative. But narrative is not her stopping point. As I learned from the artist in her Midtown New York studio, what she’s most “interested in is how flux can open the dialogue between cultural and political boundaries.” Sikander’s paintings and animated films have been exhibited internationally at the Venice Biennale; Museum of Modern Art, NY and the Whitney Biennial. Against the far window in her studio, a small leather box is stacked on top of books. Inside is the „U.S. Department of State - Medal of Arts“, recently presented to Shahzia Sikander by Hillary Clinton. . Cheryl Kaplan: When did you make your first miniature paintings? Shahzia Sikander: In 1988, I majored in miniature painting at the National College of Art in Pakistan. I was the only person in the department and studied with Bashir Ahmed. I was also interested in the conceptual miniature painter Zahoor ul Akhlaq. [Akhlaq, a Civil Rights activist and his daughter, a well-known classical dancer, were murdered in 1999.] I was curious about what miniature painting represented as a complicated craft-based residue of the English Colonial period of the school and region and its relation to tourism as well as its lack of a continuous critical history. Why doesn’t the term miniature painting explain your practice? My desire was to analyze miniature painting critically and not just make miniature paintings. I don’t know why I’ve been defined by the context of miniature painting. Maybe it’s an identity-based premise and categorization. I see it as two distinct stages. Starting in the mid-80s, I had a decade engagement with miniature painting, looking at ways to open up its discussion, not just in terms of a painterly approach, but through its scholarship. And your second decade? It’s the outcome of [my] progression as an artist that involved a distancing from miniature painting that was a natural outcome of my progression and growth as an artist. Miniature painting has become part of your “hand” or language as a painter, but you’ve also transformed into a system of thinking. My work is really about painting and thinking simultaneously and less about making works related to a genre. I’m interested in that distance between a point of origin and one’s current relationship to it; it fascinates me. Is it important to define what you’re looking at or doing with what you reference? There’s a whole myth around tradition, but how do you define tradition? Who makes tradition come into being only at a certain point in history? When you study how miniature painting has been understood and written about in art history, those definitions can be quite stale. Your work is incredibly lively, playful and luminous. I’m reminded of the diffuse paintings of Blake or Turner or Tiepolo where the viewer’s focus is constantly being moved about the canvas through interplays of light and composition. Your work contains a similar meandering and turbulence with shifting levels of luminosity. Your characters rarely stay put as they switch into their next role or iteration. In the animated projection "Nemesis" (2002) a strange creature starts out as a composite of many animals: a tiger, deer and bull and then suddenly a human figure appears in the mix only to encounter three winged devils. These creatures try to co-exist, but can’t. That’s a good way to understand the work. Regarding luminosity, early on I was looking at Bonnard and Vuillard. While I learned about color and light through miniature painting it was less about iconography and narrative and more about using materials to create space and dimension through light. From the beginning I was attracted to the abstract aspects of miniatures. A common assumption is that you work from Hindu mythology, Persian tales, and personal experience. Is this true? No. I haven’t worked with Persian tales or Hindu mythology, that’s a myth. I’m not interested in narrative based content that accompanies a lot of miniature painting. I was interested in the miniature image for its formal structure. It’s an incredible puzzle. I want to analyze it, to look at how color and line function. Today there are many younger artists in Pakistan who work with miniature painting, for example Imran Qureshi, Deutsche Bank’s "Artist of the Year" 2013. I influenced a lot of Pakistani artists and witnessed this explosion after me in miniature painting. I had a following of students. Miniature painters are now successful in biennials everywhere. Imran also worked with Bashir. When I left, Imran started teaching. In the last decade, artists who did miniature painting got support locally. Now there are powerful collectors investing in art in South Asia, India and Pakistan. This is generating a new structure and culture that’s the best thing that’s happened in terms of news about Pakistan. In what way does being a Muslim woman in the USA from Pakistan describe you or not? If you asked that question in early 2000, I was passionate about the frustrations. There was a time when I was deeply upset about having my work understood in that context and then I stopped being upset. Maybe I have more distance now, but I could care less about what it is to be a Muslim woman in the USA. Ten years ago, I had a closer relationship to my own history. It’s a complex topic in terms of contemporary work coming out of South Asia, the Mid-East, Latin countries, Europe and North America. I’m just back from a meeting in Switzerland where I’m part of the Master Jury for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2013 that represents a diverse Muslim community. I grew up Muslim, going to a Catholic school in Pakistan. But, this has nothing to do with my work. My work doesn’t deal with religion. The diversity and histories of the Muslim experience is so much about its plurality. This has always been ignored. Can you talk about your work in the Deutsche Bank Collection? It was a small edition done on tissue paper I did in Texas in early 2000s. It’s one of my favorite works, indicative of the loose drawings I continue to do. I was interested in how the ink coagulated to create a stain that might look like blood or thin layers of reptile skin or forms referring to the body that are strange contractions of human and animal forms, like a sculpture with a little bit of flesh. Brush and ink drawings are still at the forefront of my work. I do a lot of drawings and then edit them. The Deutsche Bank drawings have that sense of containment and fluidity. Those drawings are idea and form driven, made in reference to sculpture. How and when did the animated films and projections start? Did the cinematic work move from drawing and painting as a progression? SS: Drawing, painting and film happened simultaneously in early 2000. It was a natural progression to move from one to the other because I play with layers in both. Film happened naturally out of working with literal, physical layers of paper in drawings that became wall installations. The animations are first set up in Photoshop, which is organized in layers. In Pakistan, were you interested in narrative cinema? What was your relationship to film there? I grew up very aware of narrative, local cinema. Cinemas in Pakistan functioned socially, thriving in the 1950s to1970s, showing films from the East and West, then declined. Contemporary Pakistani culture still suffers from cinema’s decline. Part of your project for the 2013 Sharjah Biennial is located in a defunct cinema. The work includes three projects: a series of photographs; an animation; and a performance. The photographs are based on drawings and animations I projected in a decaying 1960s Pakistani style cinema in Khorfakkan, several hours from Sharjah, overlooking the Arabian Sea. I came across a Pakistani guard who helped build the cinema and now lives there alone. His presence is subtly incorporated into my photographs. So the guard is now a prisoner of the cinema. What happens in the animation? The three-channel animation reveals spheres that look like swarms of hair and act like flocking devices. It’s a slowly evolving dark landscape created with layered spoken voices and music by Chinese composer Du Yun. The sound conveys the human element while the animation refrains from injecting anything figurative. Your work volleys back and forth between abstraction and figuration. In animated films like "Dissonance to Detour" (2005), you create an ominous abstract grey, green and brown cluster, but, in other films you use military figures very purposefully. In 2005, I received the National Medal of Honor from the government of Pakistan that allowed me access to film Pakistan’s military school of music for my work Bending the Barrels (2009) which is about the awkward relationship between Pakistan’s military history and the Colonial period, as well as the theatrics of a military band. I made them play cherished Bollywood songs to patriotic melodies. Musical instruments, and especially the bugle appear frequently in your drawings and animated films like "The Last Post" (2010). Instruments are not only objects in your work, but they play an important role in signaling information to the viewer, acting as a prompt for them to access various historic periods of time. SS: The bugle call commemorates soldiers dying in war and a call for day’s end. The Last Post is about the East India Company’s presence in India and opium trade with China. The main character is the East India Company Man who comes to life as a composite of portraits, characters and uniforms based on the East India Army. I looked for images and characters from the Company School Painting. The music for the Last Post was composed by Du Yun whose work fuses chamber and pop music, cabaret and noise. The East India Man is presented against a Mughal façade and then sent tumbling into a world that breaks apart and shatters him. The title The Last Post refers to the collapse of the Anglo-Saxon domination over China. The protagonist appears in guises as a lurking threat in the Imperial rooms of the Mughal Empire that once ruled much of South Asia. Movement is kept simple so things can burst to become uncertain. I’ve always been interested in multiple meanings and things that don’t want to be located or defined. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment