Artwallaa is quite excited about this developemnt for multiple reasons, three of which (not all) have been put down below.

This is after a long time that Artwallaa is seeing an academic paper on Pakistan art appearing in such prestigious institutions (if you know of others. please send across. We'll surely highlight).

More importantly, international contextualisation of Pakistani greats (artists or otherwise) with other global artists is badly needed but hardly done. Most of the essays/papers are written by Pakistani authors or non-Pakistan authors, with mostly a Pakistan only contect (or in a sub-continental context). most of the foreign media coverage positions it as 'exotic / niche' art, bracketed in the 'miniature' art movement. Academic papers like below bring Pakistan art into the global narrative and create a broader understanding, appreciation and 'main streaming' of Pakistan art.

Artwallaa is also excited about this paper Bacause Artwallaa has always maintained Sadequain as the GOAT artist of the sub-continent (yes, the whole of the subcontinent!)

Enjoy

A Sadequain fan

Artwallaa

--------------------------------------------------

Symposium

The University of Chicago - Intercollegiate Art History Symposium - Globalized Perceptions: Art History in the Age of Asynchronicity - U of Chicago

Katherine Beavis, University of Chicago

Ollie Gerlach, University of Cambridge

Kaitlin Hao, Harvard College

Jin Charlie Kang, School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Zehra Naqvi, Columbia University

Brenna Tomas, Concordia University

----------------------------------------------

The Holy Sinner Sadequain - A Surrealist Absolute Reality

By: Zehra Naqvi

Source: (ANAH - Univ of Chicago initiative)

Sadequain (~1923–1987) is the artist that defined the birth of modern Pakistani art and inspired many contemporary Pakistani artists who followed suit. He witnessed the independence of India from British colonial rule, followed by the birth of his own nation all in his twenties; those experiences led to his own unique perspective on what he felt was the reality of Pakistan. As an artist, Sadequain has been frequently categorized as a disruptor who sought to represent the reality of Pakistan through dream-like, or even nightmare-like, depictions of unrealistic beings. Interestingly, his work often resembles the style of the Surrealist movement of the early 1920s, which encapsulated depictions of dreams and the subconscious through art. Although not traditionally categorized as a Surrealist, I argue that Sadequain’s Untitled (1985), figure 1, and his larger body of work could be categorized as Surrealist as defined by Rosalind Krauss and Andre Breton. Surrealism, in their definition, creates itself through the factors of the subconscious, representing reality through unreality, and using mirrors to extend the viewer's interpretation of reality all elements that Sadequain uses.1

In this paper, using Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) as a comparison, I argue that both Sadequain and Kahlo, though both rejected the notion their work was Surrealist (in Kahlo’s case) or dream-like (in Sadequain’s case) ultimately embody the true essence of Surrealism posited by Breton in the First and Second Manifestoes of Surrealism: absolute rationality through irrationality. In order to understand Sadequain’s perspective of Pakistan through his paintings, it is pivotal to grasp the nuanced complexity of his work and his own perception of the country. Describing Pakistan as a land of extremes, Sadequain chose to represent the reality of the wealth gap in Pakistan by acknowledging that people of the upper class were truly idle and unable to express themselves. Thus, they are consistently represented and covered in unrealistically dense and intricate cobwebs indicating their inability to speak their own perspective. Extending this observation to his work, Sadequain consistently portrayed the citizens of Pakistan as disfigured, unrealistic, and even, in some ways, grotesque, often through the inclusion of manipulated naturalistic symbolism.2

Creating a style that exemplified both the turmoil of reality and the insightful nature of dreams required a motif that Sadequain decided to continuously use; he turned to the Gadani Cactus, which became a repeated motif grounded in realism due to its naturally spindly and unsettling form. The cacti motif became synonymous with mankind, industrialization, and cities that all led to wealth gaps.3 While Sadequain grounded his criticism in reality, a plant, he extended the dreamlike elements of the composition and portrayed an unreality to convey his message. Thus, Sadequain chose to represent reality through unreality. Breton’s consecration of Surrealism first began due to his fascination with Freud’s analysis of dreams and the state of the subconscious, shown in the publication of the First and Second Manifestoes of Surrealism.4

Describing Surrealism as a form of absolute rationalism through the notion of unreality, Breton began to actively categorize artwork as Surrealist given its ability to portray the depths of our mind and the strange forces to illuminate our dreams.5 As such, I argue that Sadequain could be interpreted as a Surrealist through Breton’s definition. Although Sadequain has overtly said that his work does not depict dreams or falsities, rather the reality of Pakistan as a nation,6 Breton elaborates that what we see in dreams is merely a greater force portraying the realities of life.7 The dreams themselves are an almost purer form of reality than what we see in day-to-day life; this idea is not and was not accepted readily by people simply because we are taught to accept reality as presented to us and view the world through the lens of logic. As such, Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto reconfirms Sadequain’s intent to portray reality through unreality, creating truth by a universally understood medium, the image, for all of Pakistan to understand (even if some of the population is illiterate).8

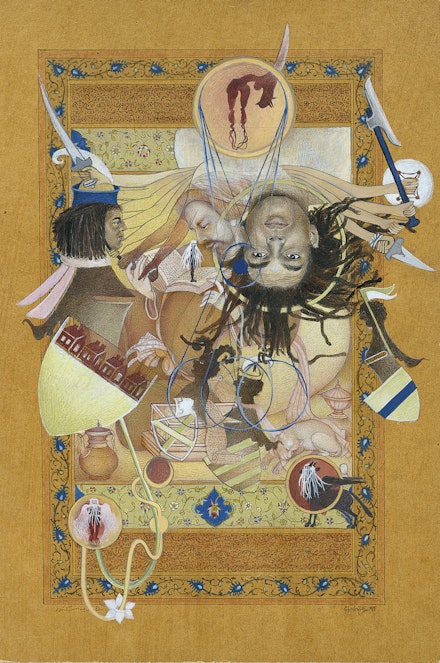

Figure 1. Untitled (Toilette Series), The Holy Sinner Sadequain, Oil and pastel on board,

1985, AAN Collection

The conditions of Surrealism outlined by Krauss can be applied to Sadequain’s fundamental artistic practices, including his paintings, calligraphy, and poetry.9 Krauss’s focus on the photographic conditions of Surrealism can be broadly interpreted as fundamental aspects of representation in artistic renderings by which people can identify artwork as Surrealist. Sadequain actively partook in two conditions as outlined by Krauss: mirroring and multiple exposures (or scales).10 Regarding mirroring, Sadequain often used a mirror as a motif in his works, one representing a transcendence into an alternate life or unreality. The focal point of this analysis, and a vivid example of his Surrealist practice, is on an Untitled work (fig. 1) in Sadequain’s Toilette Series which depicts an assumed woman revealing how this series embodies a Surrealist style defined by Breton’s manifestoes. The figure is shown unnaturally, with four arms and two profiles for a face as she dresses herself in front of a mirror while sitting on a stool surrounded by geometric objects.

The figure’s head appears draped with hair, represented in long black lines extending to the right and left. Note that on the right-hand-side, the hair extends downwards and lands near the aforementioned stool. The figure has four arms: the first connects to what appears to be their left shoulder extending downwards to the left; the second connected to the figure’s right shoulder extending to the right, though first vertically, then horizontally at the elbow; the third is on the left, jutting out of their chest and raised perpendicularly upwards, and lastly the fourth emerges out of the hair, shown vertically but ending in a horizontal extension at the elbow. Each of the apparent hands of the figure holds onto an item. The first grasps the top of a triangular vessel. The second grasps a long stylus-shaped instrument, which we can assume to be a comb. The third hand has its palm opened, facing upwards, presenting a circular vessel topped with a triangle. Lastly, the fourth extends out of the hair on the right side and re-enters into it on the figure’s left side.

In the Toilette series, Sadequain uses the mirror as an extension of the represented women’s identity. By representing the woman in reality with four arms and no representation in the assumed mirror, Sadequain purposefully alters the viewer’s automatic assumption of the mirror’s function. Rather than reflecting a reality, the mirror is inoperable and represents an unreality in itself. The duality of representation in the multiple arms as well as the opaque mirror force the viewer to consider the dual representations in reality, and not what is portrayed in the mirror. While creating some self-portraits, Sadequain would represent the process of creation, creating a mirrored effect of the art being created and the art itself.11 Regarding multiple exposures, Sadequain chooses to portray a realistic-adjacent representative figure by denoting features of a human (hands, an eye, nose, mouth, body of a human) while still slightly altering our grasp of naturalism. For instance, in Untitled, rather than one profile, the figure has two; and instead of two arms, it has four. Even more so, the background also exhibits multiple exposures by the repeated geometric motif that occurs on both the left-hand and the right-hand sides of the painting creating depth. In another rendition of the Toilette series, At Toilette, Sadequain uses a similar structure to the painting but changes the notion of reality. Rather than switching the figure’s true form itself, Sadequain manipulates the representation reflected in the mirror and depicts a shadow on the mirror’s surface. On the right-hand side, the woman’s profile is cascading towards the left and right repeatedly. In this work, the mirroring and multiple exposures (as elaborated by Krauss) are embodied by the cascading profile of the woman in the upper right-hand corner of the painting. The deviation from a traditional reflection in the mirror calls to Breton’s Surrealist Manifestos as Sadequain deliberately forces the viewer to question the reality depicted in the mirror as opposed to the naturalistic figure; which iteration or reflection are we supposed to see as reality?

Within Sadequain’s Toilette series, both Krauss’ and Breton’s Surrealist conditions are recognized and embodied by Sadequain’s unrealistic depictions of Pakistan making oneself, making identity, making country and the world possible. However, Sadequain has consistently cited his works as portraying a reality of Pakistan, one that extends beyond dreams or unnatural imagery, which contrasts with Breton’s original hypothesis of Surrealism stemming from the unconscious. In fact, Sadequain often worked without sleeping until a canvas was complete to his satisfaction, citing insomnia as a motivating factor that kept him up; thus, he was never in a dreamlike state of subconsciousness when creating his works. He was actively painting what he felt was the reality that laid beneath the surface of appearances.12 If this was the case, how can we continue to argue that Sadequain was a Surrealist?13 In comparison to Frida Kahlo, who vehemently disagreed with the notion that she was a Surrealist, I argue that while both Sadequain and Kahlo cite that their works portrayed reality and not Surrealist-dreams,14 the true intention behind Breton’s manifesto was never about whether the works of art portrayed dreams or not.

The manifestoes themselves cite using the subconscious to create a state of absolute rationalism, one free from the biases and constraints of a modern world, forcing a logical lens upon the viewer. Thus, while Surrealism is often associated with dreams and unreality, the true intention of Breton’s manifestoes was to portray reality of life at a level deeper and greater than our biased judgement; Kahlo and Sadequain both accomplish this by utilizing unnaturalistic imagery to portray their realities. Both Kahlo and Sadequain utilized this extremist view of their own reality by depicting their own realities as they saw and felt, as well as their own national identities (Mexico and Pakistan respectively). In Fulang-Chang and I, Kahlo utilizes a naturalistic self-portrait on the left side while forcing the viewer to confront themselves in the mirror on right. While there is nothing unnaturalistic about her self-portrait, the inclusion of a mirror to Breton was the embodiment of the Surrealist movement, forcing the viewer to confront their own reality or self-portrait next to Kahlo’s.

In what seems like a literal interpretation of Krauss’s photographic conditions, Kahlo’s choice to include a mirror is inherently Surrealist whether it is through the painting or a reflective surface that confronts the viewer and their conception of reality. Compared to the Untitled Toilette Series by Sadequain, the consistency of mirroring creates a deliberate link between the two works that otherwise seem entirely different. The mirror in Sadequain’s work is not functional as a reflective surface but rather, it reflects an alternate reality of the figure. Even more so, the figures of Sadequain’s work are not naturalistic. To Kahlo, this portrayal of her reality was accurate to how she felt at the time while other portraits, such as The Broken Column, utilized dream-like imagery to portray her pain post-surgery. While her pain was internal, Kahlo was able to utilize unrealistic imagery to communicate the pain within her, depicted through a broken column, nails fastened into her body, and the metallic corset that locked her into place.15 Similarly to Kahlo, Sadequain often explored the intentions of life’s suffering and chose to depict life as a passage to death through extremist renderings of unnatural states; in Self Portrait: Fasting Sadequain I (Under the Apple Tree), Sadequain emphasizes the rigidity of life by mimicking the oft-told tale of Buddha fasting under a bodhi tree and an ancient Gandharan sculpture.16 His body is shrewdly thin with his skeleton appearing outside his body aptly depicting himself as the “rotting corpse...in Death’s deep slumber;” his face remains the only naturalistic element.17

Although the title indicates it is an apple tree, the rough crosshatching across the base of each tree calls back to the Gadani Cactus motif representing the withered deterioration of life as it passes. Though Sadequain never suffered as overtly as Kahlo did due to her medical ailments, Sadequain aimed to represent the internal chaos of being and suffering through unnaturalistic imagery that is, arguably, inherently Surrealist. By portraying what exists under the surface of daily life, both Sadequain and Kahlo use Surrealist imagery to portray an absolute reality. Both utilized elements of naturalism, particularly greenery and plants, to ground their interpretations in reality and then portrayed their reality through art beyond what the eye can see in daily life: the reality that communicates their faces, their unique identities, and simultaneously the internal suffering both undertake—whether physical or mental.

Ultimately, while both Sadequain and Kahlo have argued that they only represent reality and truth, I would argue that the interpretation of Surrealism was always to portray an absolute reality through dreams; it did not necessarily mean that the painting itself was a dream; rather, it was giving the viewer a look into the subconscious truth of the artist through an alternate lens. In that regard, I believe that the initial manifestation of Surrealism (as posited by Breton) had been watered down to largely be interpreted as portraying dreams instead of portraying absolute reality through the subconscious mind. Thus, while Sadequain and Kahlo both maintained that they portrayed reality and not dreams, no matter how unrealistic their paintings were, both used unreality to express their internal strife to the otherwise logical world.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Krauss, Rosalind. “The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism.” October, vol. 19, 1981, p. 3., doi:10.2307/778652.

2 Sadequain and Bhatty, W.K.. On My Work as a Painter in Pakistan. Leonardo, The MIT Press, 1974. In his own words, Sadequain highlighted that the intention behind most of his paintings was to portray the true reality of Pakistan and how he lived life; he argued that his work should be understood as an ultimate reality not necessarily abstract or dream-like.

3 Hashmi, Salima, et al. Sadequain: The Holy Sinner. Mohatta Palace Museum in Collaboration with Unilever Pakistan, 2003.

4 Voorhies, James. “Surrealism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/surr/hd_surr.htm (October 2004).

5 Breton, Andre. From the First Manifesto of Surrealism. Art in Theory, 1900–2000, An Anthology of Changing Ideas, 1992. Breton, Andre. From the Second Manifesto of Surrealism. Art in Theory, 1900–2000, An Anthology of Changing Ideas, 1992.

6 Sadequain and Bhatty, W.K.. On My Work as a Painter in Pakistan. Leonardo, The MIT Press, 1974.

7 Breton, Andre. From the First Manifesto of Surrealism. Art in Theory, 1900–2000, An Anthology of Changing Ideas, 1992. “the depths of our mind contain within it strange forces.”

8 Sadequain and Bhatty, W.K.. On My Work as a Painter in Pakistan. Leonardo, The MIT Press, 1974. using art as a medium of connecting with a broader audience in Pakistan.

9 Naqvi, Akbar. Image & Identity: Painting and Sculpture in Pakistan, 1947–1997. Oxford Univ. Press, 2010. the scope of Sadequain’s broad artistry.

10 Sadequain and Bhatty, W.K.. On My Work as a Painter in Pakistan. Leonardo, The MIT Press, 1974.

11 Hashmi, Dadi, and Naqvi all reference Sadequain’s tendency to self-represent his process.

12 Sadequain, in his own words, argues that elaborate crow’s nests and cobwebs act as motifs for the internal struggles and evil nature of some people (using unrealism as a means to portray the truth behind a person’s intentions).

13 Hashmi, Salima, et al. Sadequain: The Holy Sinner. Mohatta Palace Museum in Collaboration with Unilever Pakistan, 2003. Sadequain suffered from insomnia whilst painting his larger works.

14 Fulang-Chang and I: Kahlo refutes Breton’s claim that her work is the embodiment and a true example of Surrealism.

15 “The Broken Column - Google Arts & Culture.” Google, Google, artsandculture.google.com/story/the-broken-column/bQJSm_lP61UwJw. The Broken Column: Kahlo’s work post-surgery encompassing her pain.

16 Dadi, Iftikhar. Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia. Univ of North Carolina Pr, 2019. Sadequain’s interest in Gandharan art particularly the collection at The Lahore Museum.

17 Hashmi, Salima, et al. Sadequain: The Holy Sinner. Mohatta Palace Museum in Collaboration with Unilever Pakistan, 2003. The Holy Sinner - quote from Sadequain’s poetry Rubaiyat of Sadequain