(Source: Title, intro and magazine shots at the bottom: Gandhara-art-Space; Main section: Asia Sciety)

Guggenheim Museum NYC's exhibition 'No Country'(Art from South and South East Asia) opens at the Asia Society Museum Hong Kong. Works by Khadim Ali and Bani Abidi represent Pakistan in this exhibition, featuring works from Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam, India and Bangladesh.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Asia Society Hong Kong Center will present No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia, the inaugural touring exhibition of the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative, from October 30, 2013, to February 16, 2014. Featuring recent work by 13 artists from Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, No Country presents some of the most compelling and innovative voices in South and Southeast Asia today. The exhibition was first seen in New York at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (February 22–May 22, 2013) as part of the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative, a multi-year collaboration that charts contemporary art practice in three geographic regions—South and Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa—and encompasses curatorial residencies, international touring exhibitions, audience-driven educational programming, and acquisitions for the Guggenheim’s permanent collection. All works have been newly acquired for the Guggenheim’s collection under the auspices of the Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund. Following its presentation in Hong Kong, the exhibition will travel to Singapore.

Bani Abidi

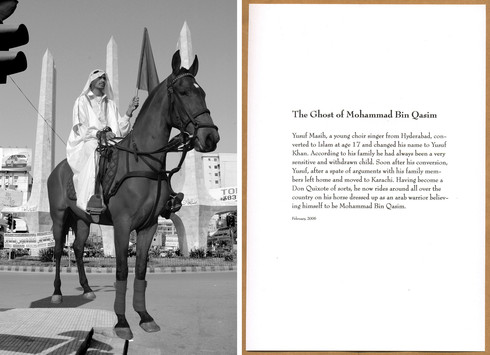

The Ghost of Mohammed Bin Qasim, 2006. Nine inkjet prints, edition 5/5, six prints: 14 1/2 × 18 1/4 inches (36.8 × 46.4 cm) each, and three prints: 18 1/4 × 14 1/2 inches (46.4 × 36.8 cm) each. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012, 2012.139.1. © Bani Abidi

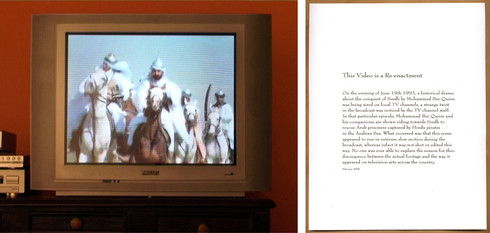

This Video Is a Reenactment, 2006. Color video, silent, 58 sec. loop, and inkjet print, edition 3/5, 18 1/4 × 14 1/2 inches (46.4 × 36.8 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012, 2012.139.2. © Bani Abidi

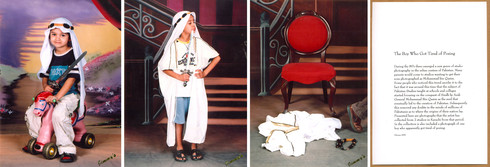

Abidi explores historical and contemporary representations of the figure of bin Qasim, and the proliferation of this narrative in state history and shared culture, through her fictional depictions of the hero in his emblematic form—wearing the Arabic keffiyeh, brandishing a sword, and riding a charging horse. In The Boy Who Got Tired of Posing, the artist plays on the trend of popular studio photography in 1980s Pakistan, which saw parents encourage their sons to dress up as bin Qasim for portrait shots. In the work’s final image, the subject, tired of performing, mischievously elects to exit the frame. In This Video is a Reenactment, the artist recalls Labbaik, a televisual dramatization of the colonial founder’s conquest, by excerpting a sequence showing the hero’s momentous horseback ride.

In Abidi’s video, however, the act is slowed down, accentuating its histrionic impact on the nation. Finally, in a suite of eight monochrome photographs, The Ghost of Mohammed Bin Qasim, the artist monumentalizes the figure, who appears to haunt various sites of national significance around Karachi including the Lahore Fort, the tomb of Emperor Jahangir, and the National Mausoleum of the founder of Pakistan, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, or Mazar-e-Quaid. Yet on closer examination, these glimpses of the return of the historical figure contain various incongruities and awkwardnesses. A short fictional text reveals the story of how the haunting began with the conversion of a young man, Yusof Masih, to Islam, and his imagining himself as bin Qasim. The figure, juxtaposed with iconic contexts, raises questions of the roles of nationhood, nationalism, and narratives of origin in the trajectory of history.

The Boy Who Got Tired of Posing, 2006. Three chromogenic prints and one inkjet print, edition 3/5, three prints: 40 3/4 × 30 3/4 inches (103.5 × 78.1 cm) each and one print: 18 1/2 × 14 1/2 inches (47 × 36.8 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012, 2012.139.3. © Bani Abidi

Khadim Ali

Untitled 1, Rustam Series, 2011–12. Watercolor, gouache, and ink on paper, 27 1/2 × 19 5/8 inches (69.9 × 49.8 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012, 2012.143. © Khadim Ali

The title of Khadim Ali’s Rustam Series (2011–12) references the hero of the Persian Shahnameh (Book of kings). The protagonist of Ferdowsi’s 11th-century epic poem is recognized for his valor and strength, but Ali’s work recalls only his name; the paintings allude to the persecution of the Hazara minority in Afghanistan and Pakistan, a community that finds itself displaced on both sides of the border. The work depicts demons, and suggests that the legendary character of the Rustam has been usurped in contemporary times as justification for hostility and bloodshed, his heroism now ascribed to those who perpetrate violence and domination. In a broader sense, the work reflects on the upheavals and crises that emerge from lingering difference.

Untitled 2, Rustam Series, 2010. Watercolor, gouache, and ink on paper, 19 5/8 × 16 3/4 inches (49.8 × 42.5 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012, 2012.144. © Khadim Ali

Successive cycles of violence and aggression are not limited to this particular minority community, but recur in oppressive circumstances elsewhere. In its reference to the narrative and lyrical traditions of the Persian people and the region, Ali’s work recollects both the triumph of civilizations past and the turmoil and aftermath of conquest. Yet in spite of loss, there linger traces of individual and cultural memory, of which the return of the Rustam is one. Layered in these works are excerpts from epic poems and literary references to Persian and Afghan history and culture, keys to meaning that the violence of contemporary conflict cannot efface. Also depicted in the series of paintings are the silent and empty alcoves in cliffs that were once occupied by the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan. Though these 6th-century statues were destroyed in 2001, their physical absence, like that of the Rustam, has a haunting aura of its own.

Untitled 3, Rustam Series, 2011–12. Watercolor, gouache, and ink on paper, 19 7/8 × 16 15/16 inches (50.5 × 43 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012, 2012.145. © Khadim Ali

Following the style of miniature painting, and in particular the technique of neem rang (half-color), the artist uses traditional methods of production including pigmentation with gold and silver leaf. This traditional South Asian aesthetic, now also marked by Persian influences, is a form of Mughal painting that was once used in illustrated texts, primarily to represent royalty, battles, and legends. The rich and sensitive detailing of these historical portraits is, like the literary epic, revived in Ali’s work, which accords the traditional practice a contemporary relevance by aligning its cultural significance with the circumstances of today.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Good sharing !!!

ReplyDeleteenglish proofreading services

Thanks...