The US-based Pakistani artist, who likes to give classic art forms a contemporary twist, is the focus of an Asia Society exhibition focusing on her progression as a painter

PUBLISHED : Monday, 21 March, 2016, 8:01pm

UPDATED : Monday, 21 March, 2016, 8:55pm

Comments:

The Asia Society in Hong Kong is staging a major retrospective of the art of Shahzia Sikander, one of the most versatile visual artists working today and recipient of the society’s award for significant contribution to contemporary art last year.

Sikander, who is Pakistani but based in the United States, first came to Hong Kong in 2009, when Para Site showed a selection of her videos. This exhibition is far broader, and focuses on her progression as a painter.

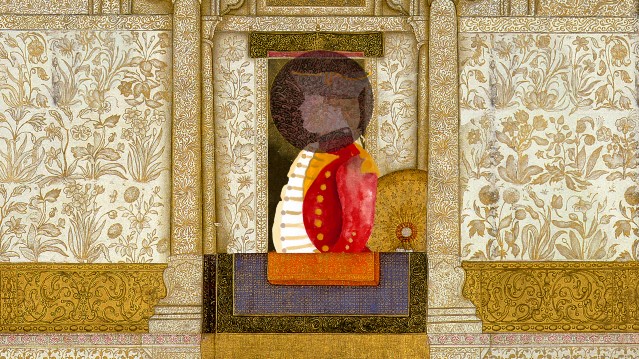

A still from Parallax (2013).

Sikander’s practice has always been grounded in drawing, and that is obvious even in the large animation called Parallax. The rich, animated imageries that she created for the 2013 Sharjah Biennial were scanned from small drawings that recall her training in Indo-Persian miniature painting.

Her work is often both a tribute to that classic art form and a challenge to its conventions. One of the earliest works on show in Hong Kong is The Scroll, from 1989-91. As the title suggests, this work is a long, horizontal scroll, which already departs from the usual diminutive format of miniatures.

She also abandoned the form’s classical heroic subject matter and opted to depict the life of a contemporary Pakistan household, based on Sikander’s own upbringing.

In each room, members of the extended family can be seen doing perfectly normal things, like packing to go on holiday or checking the contents of the refrigerator. The fine, detailed outlines, vivid colours and multiple vantage points chime with tradition; a red fence behind the house – a repeated motif in her work – represents a continuing narrative with links to history.

The Scroll, (1989-91).

History flows strongly throughout her work. It is in the brown tint of the paper used for The Scroll, stained as it is with tea, a commodity inseparable from British colonial power; in the figure of The Company Man who shows up repeatedly in her work, a pot-bellied employee of the East India Company who helped build an empire; in the Hindu icons she appropriates, images that would have been radical when she was growing up under the military dictatorship of President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who was intent on Islamising Pakistan.

At the same time, a counter narrative provided by Sikander’s personal history often challenges the generality of the big historic backdrops. The artist grew up a Muslim, attended a Catholic school, and was fortunate to come from a liberal, well-educated household that believed in empowering its women despite General Zia’s introduction of new ways to oppress women.

“In public, the whole country was being homogenised at a time when a lot of different people had just moved to Pakistan after Partition [in 1947, when Pakistan and India were created with British India’s independence]. For example, religion was being institutionalised. But in private, it was very different,” she says.

She also found when she moved to theUS in the 1990s that she wasn’t fitting into easy categories either. “I decided the experience of the diaspora wasn’t for me. It was my choice to move there. I am comfortable in my skin. It’s only a slight dislocation,” she says.

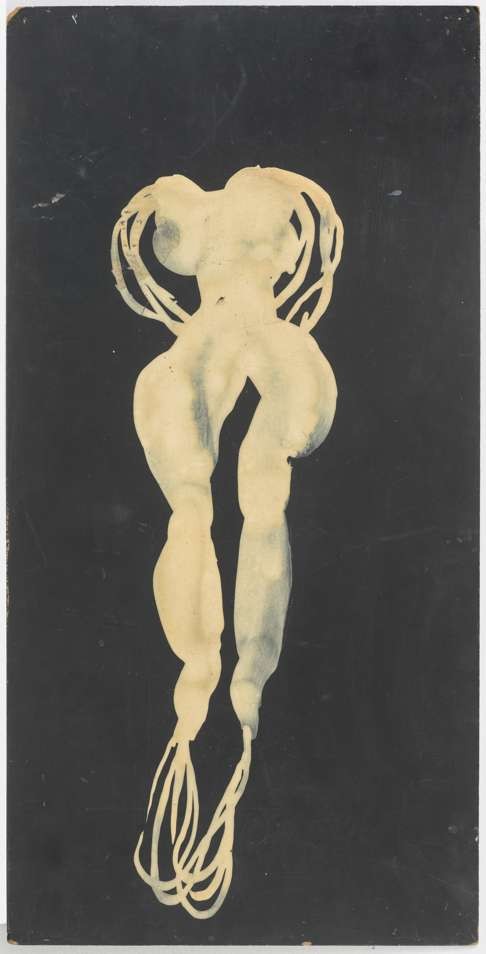

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation (1993).

And so she painted A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation (1993), an abstract figure of a woman floating through a dark space that bears little resemblance to earlier works. That a Pakistani would use the two words – pleasing and dislocation – together is pointed, given the deep scars left behind by Partition.

“My grandparents made a lot of sacrifices because of Partition and I grew up listening to them talking about it and I respect that,” the artist says. “Personally, Partition has also meant that I couldn’t go to India to study the miniatures there, and it’s been very difficult for me. Segregation also heightened the sense of the other.”

The one good thing about what one of the faux propaganda posters in the show describes as “a spontaneous response to a difficult situation” is that Muslims like herself can grow up as first-class citizens, she adds.

That figure in the 1993 work, partly inspired by her exposure to graffiti artists and wall paintings in America, keeps surfacing in subsequent works.

Like the Company Man, it is just one of a number of memorable symbols she employs. Another one is the gopi’s hair – the topknot worn by a female follower of the Hindu deity Krishna. In her paintings and in animations, the gopi’s hair has a life of its own, often flying in flocks, like crows, giving new associations to yet another traditional icon

A still from The Last Post (2010).

She has observed that Hong Kong is struggling to define its relationship with its colonial history. “It is inevitable that we will always be casting for a relationship with the colonisers. But post-colonialism is like the nature of my work. Fluidity is part of it,” she says.

A section of her work is also being shown at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum, an apt setting for her contemplation of empire, trade and the fluidity of identities.

Shahzia Sikander: Apparatus of Power, Chantal Miller Gallery, Asia Society Hong Kong Centre, 9 Justice Drive, Admiralty, Tue-Sun, 11am-6pm and 11am-8pm during Art Basel Hong Kong (Mar 22-26). Ends July 9