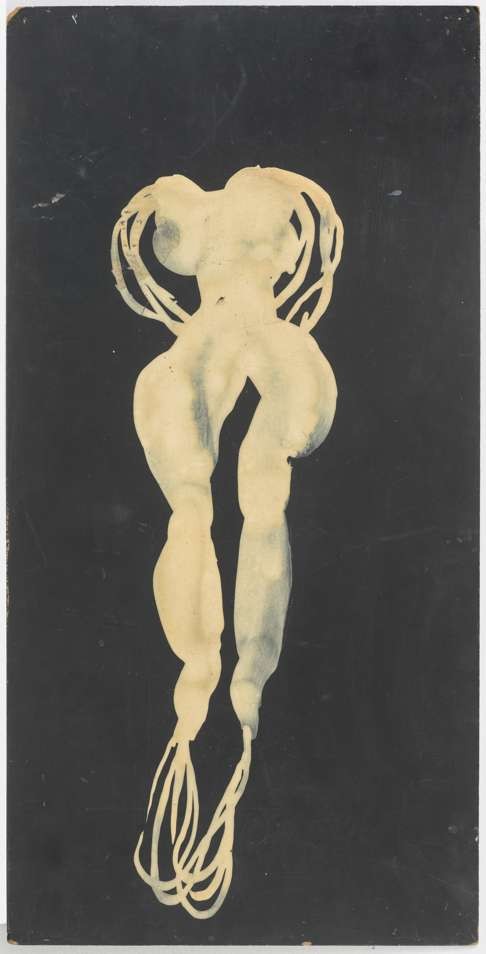

Portrait of the Artist (Ayad Akhter) by Shahzia Sikandar (Courtesy - AAN Collection)

The Incantatory Power of Ayad Akhtar and Shahzia Sikander

The two artistic geniuses—a novelist and a visual artist—discuss US politics, Islamophobia, and their recent work.

By Ayad Akhtar and Shahzia Sikander

Source: The Nation

SEPTEMBER 15, 2020

Novelist Ayad Akhtar, left, and artist Shahzia Sikander, right, discuss their artistic collaborations. (Photos courtesy of author / Vincent Tullo/ Werner Bartsch)

In an age of visual profusion, when the vividness and abundance of images consumed for distraction and commerce is breathtaking, it might seem naive for an artist to try to create images of incantatory, even magical power. To seek a holy relationship to the image today is often seen as foolhardy.

In the Western tradition, before the Renaissance and Reformation, images were the vehicle of presence; they could summon a saint into being. Observers stood in veneration, seeking intercession, dialogue, wisdom; an image was the basis of a relationship with an order of experience far deeper than aesthetic appreciation.

The extraordinary and unique work of Shahzia Sikander proceeds from a faith in this primal power of the image, and in the belief of an artist as a seer. It is a timeless faith, at odds with our accelerated times, which only makes Sikander’s commitment to plumbing the mysterious power of images all the more remarkable.

Over the course of her career, Sikander’s image production has grown at once more subtle and more encompassing. Her reclaiming of the iconography of the Prophet from the historical Indo-Persian painting canon, replete with representations of the otherworldly and its angelic hosts, is more than just a nod to a historical mythos. It is an ensign signaling her profoundest ambition: to reclaim the mythic and sublime not as modes of commentary, or even of expression, but as gateways to experience itself.

In 2015, Sikander reached out to me with an idea to collaborate on a project she was working on. A conversation started, and slowly, we began to work together. Most recently, Sikander has penned portraits based on characters in my new book, Homeland Elegies.

Sikander and I wrote our own questions to guide our conversation about art, Islam, and politics.

—Ayad Akhtar

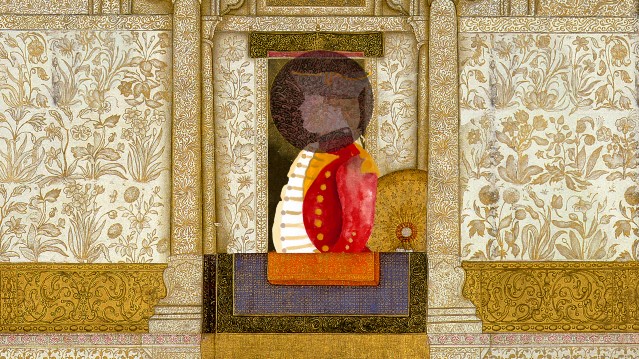

A detail of Shahzia Sikander’s Ecstasy as Sublime, Heart as Vector mosaic at Princeton University.

How did you meet?

AYAD AKHTAR: Shahzia, I have been an admirer of your work for years. When you reached out to me, unbidden, four years ago I was gobsmacked.

SHAHZIA SIKANDER: I’m not sure what drove me to reach out to you, other than a deep intuition that what drives your work was more than relevant to my own ongoing research. I could sense there was much for us to discuss. I sensed an artist who was plumbing the depths of a heritage we both share—and doing so caught between worlds, between artistic vocabularies, between cultures, practices, histories. I suppose I also felt a kind of kinship with you. We could’ve easily met in Pakistan, in a mutual family friend’s aunt’s home in Rawalpindi or Abbottabad. Oddly, in your new novel, you depict a scene in which you are in the latter city in 2009, when I was also there, filming Bending the Barrels at the military academy.

How did your collaboration begin?

SS: I thought you might be interested in matters of representation and identity—

AA: And I was resolutely not interested in that!

SS: Which I figured out soon enough. But it got us on the subject of Islamic philosophy, spirituality, and the Prophet.

AA: Which is a subject I am often on. One of the things that I find fascinating is how little people are interested in approaching the Prophet as a literary construction. Which is so different from how the Old Testament is now read: where we can approach it as a literary text, with its major figures operating as characters in a story, where we can extract literary and sociological meaning from the narrative and linguistic construction. It’s so clear that the construction of the Prophet’s identity is rich with exactly these kinds of valences, and they are mostly lost because there is so little interest in reading the Quran that way.

SS: The conversation led to the topic of the miraj, in particular its role in Muslim traditions and the complexities inherent in his imagination and depiction, both in Islamic lands and in the West.

Two of four Portrait of the Artist etchings by Shahzia Sikander that accompany text by Ayad Akhtar.

AA: Just to clarify, miraj is the tradition of the Prophet’s miraculous journey into the celestial realms, all of which took place over the course of a single night. Interestingly enough, some have seen the tradition of miraj as part of Dante’s inspiration for his Divine Comedy.

SS: The resulting collaboration, a series of four etchings titled Portrait of the Artist and Breath of Miraj, provides a lyrical interpretation of the Prophet’s celestial ascent. For me, this work was rather uncanny in its timing: I won the Princeton commission around that moment and also started researching several historical miraj paintings with the art historian John Seyller such as the Ilkhanid paintings held in the Topkapı Palace Library in Istanbul, the Timurid miraj paintings in the David Collection in Copenhagen, and the ascension painting attributed to Sultan Muhammad from Khamsa of Nizami, Tabriz Iran, in the British Library. The more I studied the various historical miraj paintings, the more I connected I felt to the visual, stylistic, and emotional intelligence of the works. It was a deeply moving experience. Then I had the epiphany to incorporate the ascension motif in the Princeton mosaic, with the hope to inject a visceral and powerful experience for the viewer.

AA: And to stick an effigy of me into the middle of it!

SS: You didn’t stop me! [Laughing] To clarify, it’s in a separate section of the tripartite related to life and death.