"Presented together for the first time with Mughal counterparts, this selection of drawings signals Rembrandt’s fascination with exceptional Indian artifice as well as elucidates his own artistic practice"

Credit: Getty Museum

Rembrandt as you’ve never seen him before.

Left: Shah Jahan (detail), about 1656–61, Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. Dark brown ink and dark brown wash with scratching out on Asian paper toned with light brown wash. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1978.38. Image © The Cleveland Museum of Art Right: Jujhar Singh Bundela Kneels in Submission to Shah Jahan (folio from Minto Album; detail), 1630–40, Bichitr. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library. Image © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, CBL In 07A.16

Left: Shah Jahan (detail), about 1656–61, Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. Dark brown ink and dark brown wash with scratching out on Asian paper toned with light brown wash. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1978.38. Image © The Cleveland Museum of Art Right: Jujhar Singh Bundela Kneels in Submission to Shah Jahan (folio from Minto Album; detail), 1630–40, Bichitr. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library. Image © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, CBL In 07A.16

IN AN INTRIGUING MOMENT LATE IN HIS CAREER, Rembrandt created a series of unusually meticulous drawings depicting emperors and courtiers from Mughal India. This exhibition explores the Dutch master’s careful studies of imperial Mughal portraiture and places them within a broader circuit of cross-cultural exchanges. By juxtaposing Rembrandt’s drawings with Indian paintings of similar compositions—and pairing Mughal artworks with European prints that inspired them—fascinating stories unfold about the flow of art and ideas across time and oceans.

Shah Jahan and his Son, about 1656–61, Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. Brown ink and brown wash with scratching out on Asian paper toned with light brown wash. The Rijksmuseum, gift of J.G. Bruijn-van der Leeuw, Muri, Switzerland. Image: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India

The twenty-three surviving drawings Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) made of Mughal emperors, princes, and courtiers mark a watershed moment, when the Dutch master responded to art of a dramatically different culture. Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India considers the unique significance of these cross-cultural works in the context of seventeenth-century global exchange. What motivated Rembrandt to study Mughal portraits? Did he own an album of them? Can we trace his drawings to specific, surviving artworks imported into Amsterdam from the Dutch trading post in India? This exhibition reveals the critical eye and attentive curiosity he turned toward Mughal portrait conventions. For Rembrandt, the art of Mughal India was not merely a foreign curiosity. It carried certain associations of empire, trade, luxury, and artistic skill.

Rembrandt and Global Amsterdam

With the establishment of the Dutch East India Company, or Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), in 1602, the Dutch forged a dominant presence in the lucrative spice trade. This international trade network brought large quantities of foreign art and artifacts to Amsterdam. The 1656 inventory of Rembrandt’s possessions describes a collection of art objects from around the globe, including items from Mughal India. The Mughal Empire in Rembrandt’s time covered a vast area that today would encompass Afghanistan, Bangladesh, much of western Pakistan, and all of northern and central India. Mughal emperors traced their lineage back to Timur, the Turco-Mongol conqueror and founder of the Timurid Empire of Iran and Central Asia. Portraits promoting Mughal rulers’ wealth, political aspirations, and Islamic faith came to the Netherlands on VOC ships embarking from the Indian port of Surat. Possibly owned by a VOC official in Rembrandt’s circle, these meticulous portrayals of imperial magnificence sparked the artist’s imagination. Dutch merchants, collectors, and other artists would have recognized Rembrandt’s drawings after Mughal paintings as a demonstration of his international and refined taste.

Rembrandt’s Indian Sources

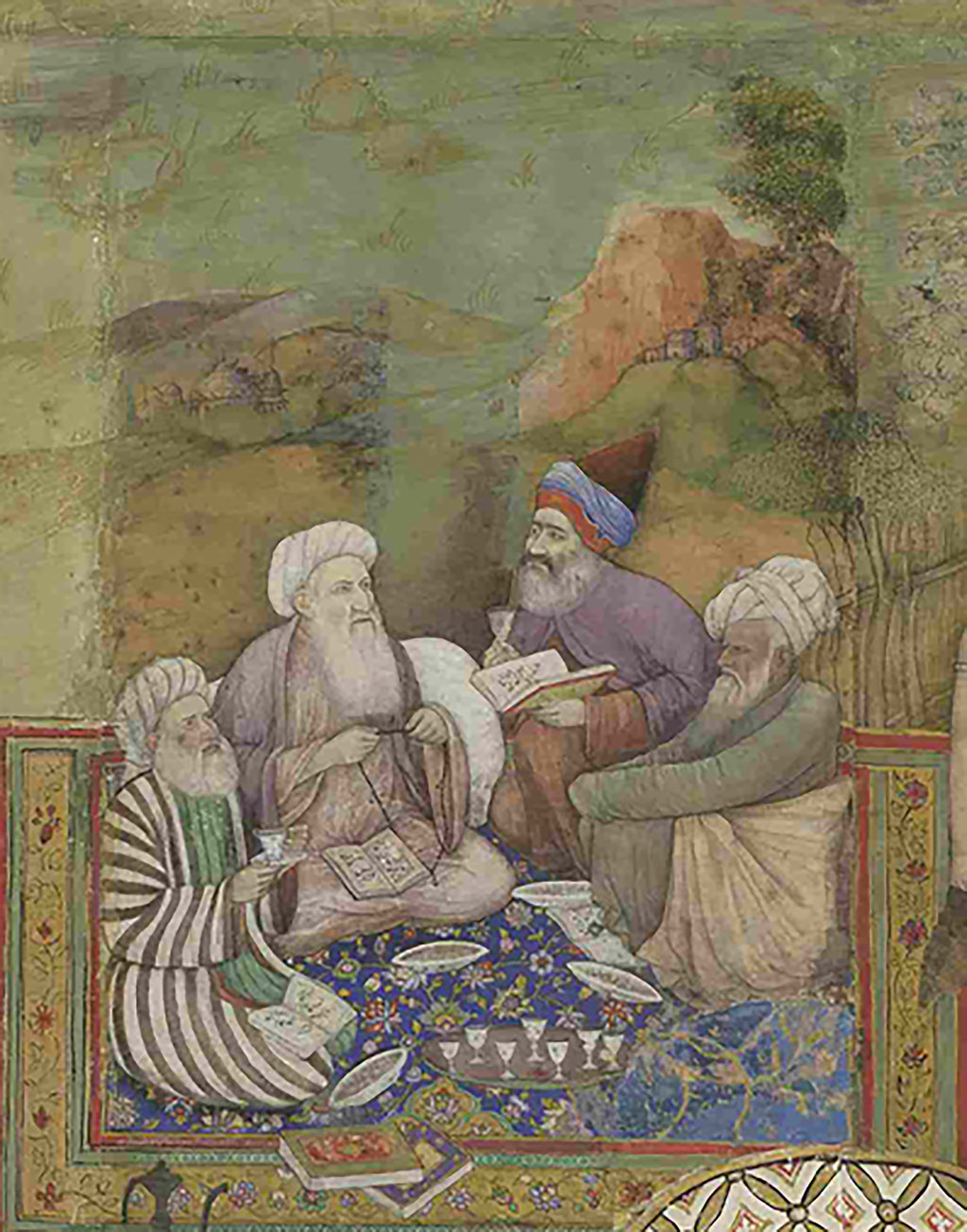

Rembrandt’s drawings inspired by Mughal portraits prove visually that he had access to imperial paintings made between 1610 and 1655. Because Mughal workshops produced many versions of a popular composition, it is difficult to identify exactly which Indian works served as Rembrandt’s sources. Some scholars believe that his models included numerous Mughal and Deccani paintings formerly owned by seventeenth-century Dutch collectors, now in part of decorative collages in Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna. Rembrandt’s drawing of four Muslim mullahs seated outdoors clearly matches a painting found in Schönbrunn Palace (see below). But most of his compositions are not based on those at Schönbrunn, but are instead located elsewhere.

European Art in Imperial Ateliers

Long before Rembrandt made his drawings of Mughal aristocrats, Dutch merchants employed art to facilitate trade in Asia. In 1597, a Dutch ship sank en route to China. Among the treasures found in the wreckage was a startling discovery: a package containing four hundred prints by and after Dutch and Flemish artists. Prints particularly appealed to Mughal court artists, who were accustomed to working with single-tone drawing and calligraphy. Artists in imperial workshops adapted European prints to fit the international ambitions of their patrons, as evidenced in the Indian version of a Roman hero inspired by prints by Dutch artist Hendrick Goltzius (see below). The pairing of Mughal paintings with European prints in this exhibition—including portraits of rulers and genre scenes—parallels the cultural and artistic complexities at play in Rembrandt’s drawn copies.

Jahangir and the Taste for European Art

Jahangir, about 1630–35, Muhammad Mushin, opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Private collection.

Rembrandt’s creative copies feature many Mughal emperors, including the great patron of the arts, Jahangir. Born with the name Salim, Jahangir followed the royal practice of adopting honorific titles, identifying himself as “World Seizer” upon his accession to the throne in 1605. Fond of portraiture, nature studies, and landscapes, the emperor took pride in regarding himself as a connoisseur. He not only collected and displayed European paintings, but also employed Dutch artists for their artistic skills. By encouraging a synthesis of artistic styles, Jahangir broadcasted his cosmopolitanism and glorified his reign.

Rembrandt and Shah Jahan

A Mughal Nobleman on Horseback (Shah Jahan), about 1656–61, Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. Brown ink and brown and gray wash, red chalk wash and red and yellow chalk on Asian paper lightly toned with light brown wash. The British Museum, London, bequeathed by Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved

Jahangir’s son Shah Jahan ruled Mughal India from 1627 to 1658, spanning the years that Rembrandt worked in Leiden and Amsterdam. In eight portrait drawings of Shah Jahan—more than he made of any other Mughal ruler—Rembrandt carefully studied the trappings of imperial magnificence. The poetic claims that Shah Jahan was the “King of Kings under Heaven” and the “Royal Rider on the Piebald Steed of the World” were not lost on Rembrandt. He depicted the Mughal emperor with a brilliant aureole, or halo, demarcating his divine rule on earth, and created two portraits of him on horseback.

Rembrandt and Mughal Magnificence

Presented together for the first time with Mughal counterparts, this selection of drawings signals Rembrandt’s fascination with exceptional Indian artifice as well as elucidates his own artistic practice. At the final stage of his career, Rembrandt tried his hand at almost every category of portraiture and frequently included depictions of fanciful costumes. In contrast, his drawn portraits carefully imitate the facial features, clothing, jewelry, footwear, turbans, and weapons of Mughal rulers, and constitute the largest group of his copies after other works of art. They are also his only surviving drawings made on expensive Asian paper, which underscores their importance. Rembrandt and the Indian court painters who inspired him operated in completely different worlds. Their differences served to spark inventive new works, enabling these artists to reflect upon and enrich their own familiar artistic practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment