Source: Ocula Magazine

Khadim Ali's Invisible Border Expands Tradition

PUBLISHED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH INSTITUTE OF MODERN ART, BRISBANE

In Conversation with

Liz Nowell

Brisbane, 20 May 2021

Khadim Ali. Courtesy Institute of Modern Art. Photo: Rhett Hammerton

Graduating from the National College of Arts in Lahore in 2003, Khadim Ali's practice initially focused on traditional miniature painting before expanding in media and scale.

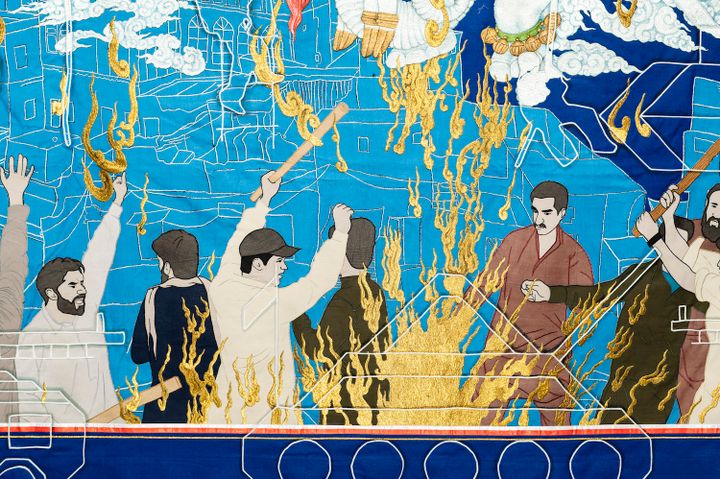

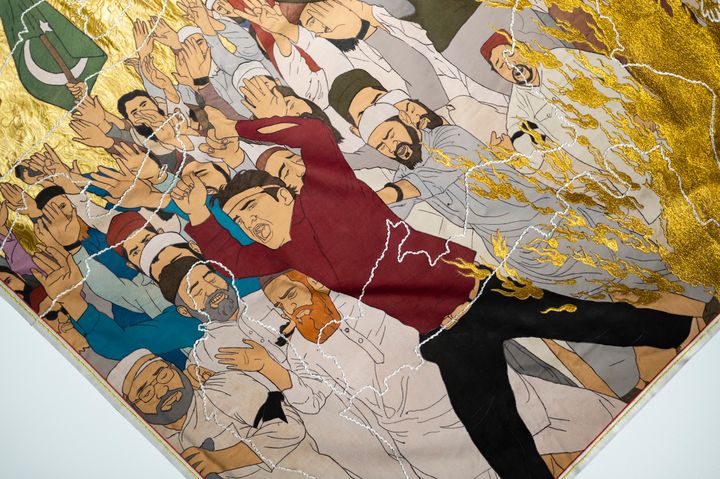

Born in Quetta, Pakistan, and now based in Sydney, the artist's practice has attracted global acclaim for works that explore life in exile. At the Institute of Modern Art (IMA), the artist's exhibition Invisible Border (10 April–5 June 2021) is his largest in Australia to date, and explores the normalisation of war and the experiences of refugees through a phenomenal body of work, including the nine-metre-long tapestry Invisible Border 1 (2021), hand-woven by a community of Hazara men and women.

Ali's interest in tapestries developed soon after his parents' house in Quetta was destroyed by a car bomb. Amongst the rubble and debris that was left over, a collection of rugs remained perfectly intact, miraculously able to withstand the terror that was reigned upon the community. In this new large-scale tapestry work and the other work in this exhibition, Ali explores the impact of war, trauma, and displacement, drawing parallels from the book of The Shahnameh, Persian literature, current politics, and a whole range of sources, which he discusses in this conversation.

In this conversation, which was transcribed from a talk held at the Institute of Modern Art on the exhibition's opening day, Ali speaks with IMA Executive Director Liz Nowell about the development of his latest body of work.Over the last decade, Ali's work has been presented at institutions and galleries worldwide, including the Venice Biennale in 2009, documenta 13 in 2012, the Dhaka Art Summit in 2018, and, recently, the Sharjah Biennial in 2019, where, among his series of works titled 'Flowers of Evil' (2019), he presented a mural at Emirates Fine Arts Society painted in the miniaturist tradition, depicting a row of blue demons against a fiery landscape, eucalyptus branches hanging overhead, as a reflection on the normalisation of violence.

LNYour work draws from global events and history, but it's also very much rooted in lived experience. Perhaps you could start by telling us a bit about your life and how you've come to be in this room with us today?

KAI was born at the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan in a town called Quetta. It's not a city, but a very small town, which was mostly established during the colonisation of India. The army predominantly lived there, and so did many Hazaras.

My grandfather was in the British Army before the Parishad of Pakistan and India. After the Parishad, he chose to live on the border of Pakistan, in the hope that one day Afghanistan would have a fair government and he could go back and reclaim his land. Sadly, that never happened, and today more than half a million Hazaras are living there.

While growing up, we didn't have TV or radio or any other source of entertainment: instead, our nights were filled with stories. I vividly remember my grandfather singing from The Shahnameh. The Shahnameh was written in 1010 AD in the court of Mahmud of Ghazni in Afghanistan. It's an epic poem about the good and bad sides of humanity; about heroes and demons.

When I went to school, I found out that I looked different to other kids and spoke a different language. They looked at me differently, and I looked at them differently. It was when I went to high school that I realised we were migrants and a minority.

I was also working from a studio in Kabul, which I still have, and I was thinking about how to switch to a medium resilient enough to survive a bomb blast. So that's when I began rug weaving.

In 1994, when the Taliban established their group in Afghanistan, Quetta was one of their major recruitment points, as a border town. So I left Quetta, and went to Iran.

In Iran, I started working alongside a person who was painting propaganda murals. He was so ashamed of himself that he asked me to paint them because I was unknown in the country. So, in around 1995 or 1996, I started painting propaganda murals, until I was deported back to Pakistan in 1998. There, I enrolled at the National College of Arts in Lahore. And since around 2010 I've been based in Sydney.

LNYou mentioned that you are Hazara. Perhaps you could speak a little bit about the current experience for the Hazara community in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and, in fact, all over the world, as a very displaced people who have faced much persecution, and also about the impact that the Taliban has had on that community for such a long time now.

KAGeographically, most Hazaras are based in central Afghanistan, but after a third major massacre in the 1890s, most Hazaras fled. Sixty-two percent of Hazaras were massacred in 1890s. And it was a time when the Hazaras were seeking asylum in neighbouring countries. Now there's close to a million Hazaras living in Pakistan and almost two million Hazaras living in Iran.

In the town that I was born in, Quetta, more than 2,000 Hazaras have been killed since 2000 and the government of Pakistan is turning a blind eye to this ongoing genocide.

The same is happening in Iran. Hazaras have lived there for more than 50 years. They're still considered refugees and whenever they're caught, they're sent back to or deported to Afghanistan. In Afghanistan, there is this disguised or invisible border where they cannot avail most of the opportunities there. There's no other hope for them, and the consequence is that more than 20 percent of Hazaras are living outside of Afghanistan, in Australia and many other European countries.

LNThis new iteration of your practice demonstrates a shift from miniature painting to very ambitious large-scale tapestries and embroideries. Whilst they require you to stand back and take the entire visual experience in, they are also filled with exquisite detail and craftsmanship that need to be experienced up close.

What's interesting about this body of work is that while you have really amplified the scale, you haven't lost the level of detail and care in earlier works on paper. Perhaps you could talk a little bit about miniature painting and how you have expanded on this to incorporate installation, textile works, and sculpture?

KAMy first encounter with art was the illustrations in The Shahnameh. As a child, they ignited the landscape of my imagination with a sky, mountains, land, trees, birds, and other animals. It was so poetic; so three dimensional.

Later, in Iran, I was working on mural paintings that were very two dimensional: very much post-Russian revolutionary style propaganda posters.

When I went back to Pakistan, I was offered a scholarship at the National College of Arts, and I found out that miniature painting was a course major. I remember being so happy that the medium from my childhood imagination was now being offered at art school. After I graduated, I kept practicing miniature painting, which is very, very precise and focused. It's a court-bound tradition. You can't get around certain conventions.

There are a bunch of miniature painters in Afghanistan. They always discuss the tradition, and there are people who want to continue that, but I wanted to be known as an artist, and not labelled as a miniature painter. So I started to explore bigger works and ways to translate this medium to a new scale.

The studio that I had in Quetta, Pakistan, was also my parents' house and was blown away by a car suicide bomber in 2011. We lost everything, including The Shahnameh, which was handwritten, and one of the few things that my grandfather had brought from Afghanistan. The only thing that survived was a pair of tapestries that were given to my mother as a gift from my grandmother.

I was also working from a studio in Kabul, which I still have, and I was thinking about how to switch to a medium resilient enough to survive a bomb blast. So that's when I began rug weaving. After that, I moved onto embroidery, which I was able to make collaboratively with an embroiderer. She could take it home, work from there, and bring it back to me. And then later I could assemble each piece and make a large collage: this is how I'm working now.

LNIt's interesting that you talk about miniature painting having so many conventions that govern the craft. It is a very traditional art form, but so is rug-making, weaving, and embroidery. So in a way, though the scale is very different, there is a really clear connection in your work between contemporary ideas and traditional art forms.

KA...it's a very personal practice. It's like a personal religion, and a very personal conversation with myself. I try not to think about the final presentation of the work or what I would say if it were displayed in the gallery.

LNWhen I think about these works, I can't help but think about Afghan war rugs, which arose out of post-Soviet Afghanistan and depict the apparatus of war. You can find war rugs depicting drones and 9-11, and they were initially conceived, I believe, as tourist items for Soviet troops, but it's a tradition that has continued to this day. The stitched forms that are overlayed on these embroideries strongly reference the visual language of those war rugs.

KAThe war rugs started at the refugee camps and evolved very organically. Initially, the imagery was drawn from schoolchildren who were learning that 'A is for Allah, J is for Jihad, and K is for Kalashnikov'. And the math book was one grenade, two grenades, three bullets, four rifles, and so on.

And then these kids actually brought those images from their books and transferred them to tapestries. From there, entire war rug factories started arising, and now it's very, very commercial.

LNSomething seemingly very innocent—in the sense of it coming from the imagination of children—is also deeply political. Obviously, we talk about the personal being political, and your work really traverses that territory.

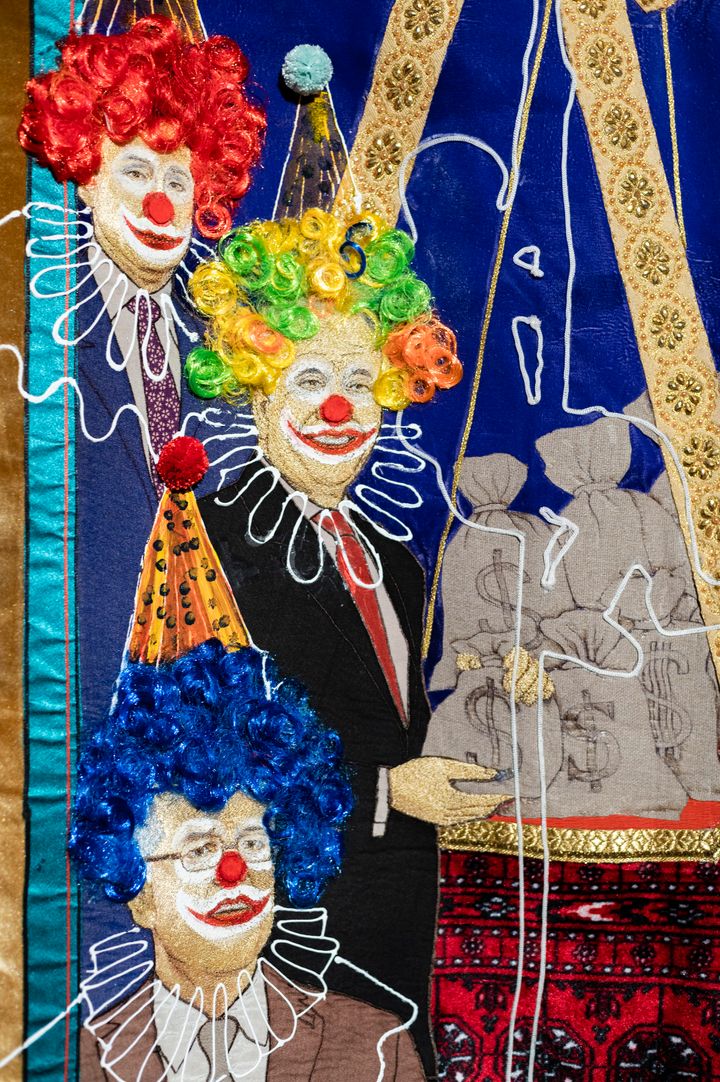

I'm interested in your journey from mural painter, to art student, to an internationally renowned artist creating works where, for example, you are depicting Donald Trump in a clown costume. It's quite a journey. When did you consciously start thinking about bringing political ideas into your work?

KAI'm a little reluctant to call myself an artist. I prefer to think of myself as using a visual diary as a means to document these moments in history, and my own personal history.

During the presidential election of America, I was very hopeful about the situation in Afghanistan. I was hoping that eventually we would get some kind of peace in Afghanistan, and I'd be able to return there to practice my art. But that turned into a modern melancholy, which just made me more hopeless and disappointed for the future, not only of Afghanistan or my own, but also of my family's future.

Wherever you live, you could turn on the TV and hear about Donald Trump and the impact he was having on the rest of the world. He gave power back to the Taliban: and now the West and the Taliban are gathered at one table talking about peace, but really, they are just trying to rule Afghanistan again.

LNWe've spoken in the past about the sensitivity of shipping your work from Kabul to Australia, given the political imagery you imply. Do you ever feel apprehensive speaking out about these issues, or do you feel a sense of duty to shed light on some of the personal and collective experiences of Hazara people?

KAWell, I only feel this responsibility when my work is on the wall of a gallery. Before that, I don't think about that responsibility at all, thus I'm very nervous or reluctant to talk about these works.

Like Invisible Border 4 (2020), which has Donald Trump in the middle. And every day, when I was looking at Donald Trump, I was like, 'I will never ever display it in a gallery,' questioning whether people would target me or not. I opened the work in Sydney and I didn't feel like going into the studio. I tried to cover his face, which is still visible.

But yeah, it's a very personal practice. It's like a personal religion, and a very personal conversation with myself. I try not to think about the final presentation of the work or what I would say if it were displayed in the gallery. When the work is finished, there's another anxiety that appears, about how I would face the audience about it.

LNLet's talk about Invisible Border 1. You were sending me photos on WhatsApp of the work in development, and I could very clearly see Scott Morrison and Donald Trump. And then when the work arrived in Sydney, you said to me, 'I can't look at these people anymore.' And so you stitched red noses and clown wigs over their faces and hair. It was quite a violent and absurd act at the same time.

What really interests me about this work, and many others in this exhibition, is the kind of melding, or layering of different cultural references, stories, and objects. For example, a 17th-century Mughal painting from the British Museum collection. Could you share the story of this work?

KAThe reference that I took for this work is a Mughal King in the 16th century who weighed his son—the prince—in gold and then gave that gold away to the village. I was looking at the king standing on the symbol of peace, which was an image of a lion and a lamb next to each other, and then at the same time I was thinking about the peace deal in Afghanistan.

I was thinking about the Taliban and how they came to the surface: they are children of the West. They were created by Westerners in Afghanistan to fight the Soviets at that time. And then after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, these terrorist organisations were left with no exit plan.

Tonnes and tonnes of weapons came into their control and they were left there with their own fate, and they started playing with the fate of minorities in Afghanistan. Then, all of a sudden, Donald Trump adopted them again and brought them back into power.

I was trying to give them a presentable look—something that people could look at or something that they could fit into the style of the art. Otherwise, it's very difficult to depict this concept of a peace deal. The entire concept of this peace deal is very ugly. It's very difficult to sugarcoat them visually to make them presentable.

LN

You mentioned the original story of the emperor weighing his son on his fifteenth birthday and giving out the coins to the community as an act of charity and celebration. And in this work, Donald Trump is weighing a leader of the Taliban for bags of money while global leaders look on. It says a lot, I think, about the economics of war and war profiteering that goes on across the world.

KAI'm a little reluctant to call myself an artist. I prefer to think of myself as using a visual diary as a means to document these moments in history, and my own personal history.

LNIt also makes me think of the work Urbicide 2 (2021), in the room next door, which is the second iteration of a work that was first shown at the Sharjah Biennial. The installation comprises 11 horns that blare Taliban propaganda CDs purchased in Kabul. And behind each of those horns is a series of Persian rugs embellished with circuitry patterns that sprawl out like a network, like a Metro line, across the room.

You and I have spoken a lot about the changing nature of work in Afghanistan and the transition from traditional crafts to electronics—explosive making and circuitry: all of which aid warfare. Perhaps you could speak a little bit about the shift that is happening in Afghanistan and elsewhere across South Asia and the Middle East?

KAUrbicide is a collaborative work between Asad Buda, Sher Ali, myself, and an iconic Hazara singer.

The design of the horns references the Islamic war helmet, which is very flamboyant with Islamic patterns on it. Each horn is playing Taliban propaganda songs, which began being distributed in 2018 after the first peace talk. My assistant and I collected some CDs of Taliban propaganda songs and I took all the songs and sat with a sound designer to design them. Asad Buda, who is a writer, wrote the text for Urbicide, which references the killing of a city. The entire text is very poetic.

The circuitry design on the wall is by Afghan artist Sher Ali, who is referencing Mujahideen jackets. In the 1970s, when they were fighting the Russians, the jackets were designed with golden thread. Now the Taliban wear plain black or white clothes. Ali took all those golden threads and mirrors and turned them into a circuit board, to make a statement about how the Taliban's medium has changed, and how they are dealing with the modern medium of war.

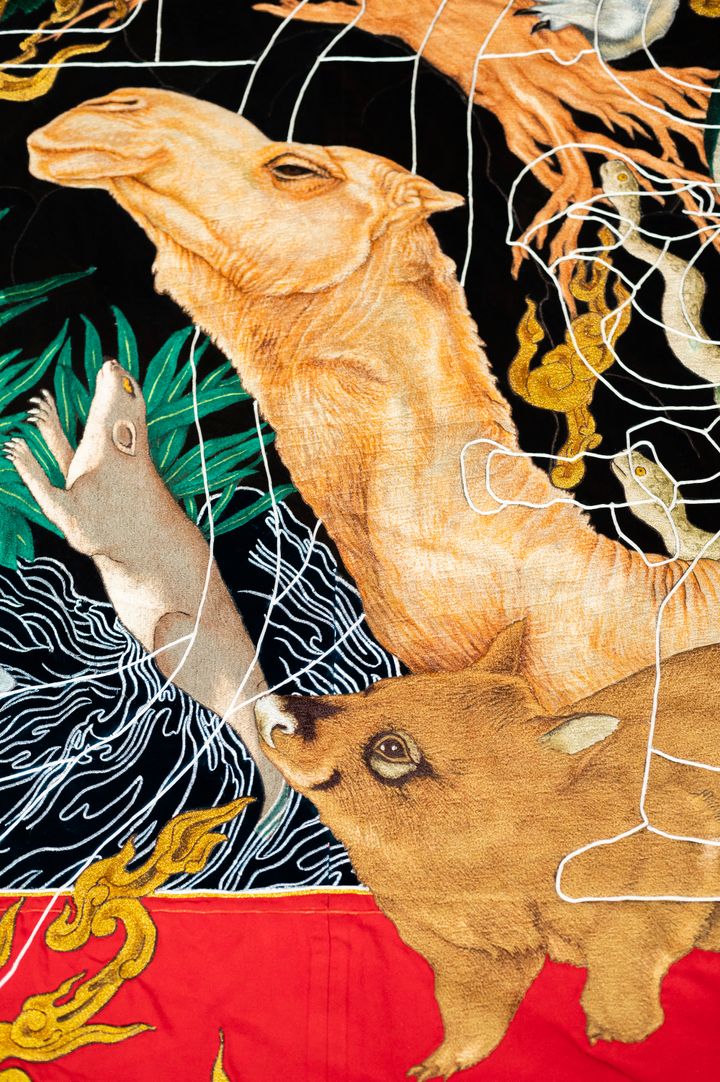

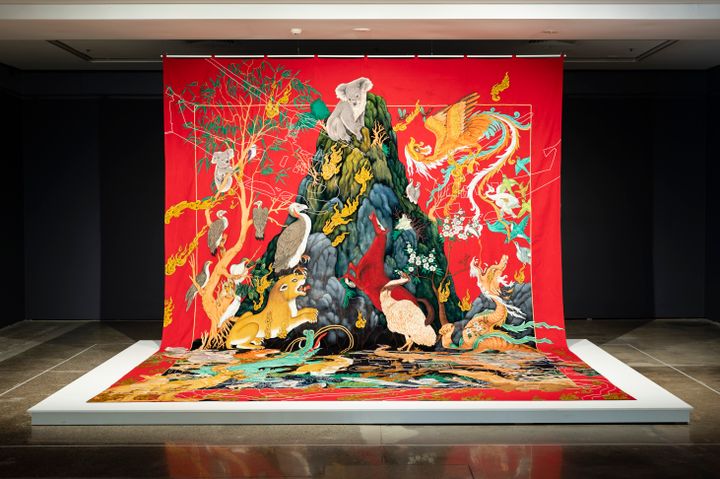

LNSermon on the Mount is a large-scale tapestry in the first room that depicts a koala atop a hill speaking to a group of animals fleeing towards the mountain. Seeing you incorporate quotidian Australian imagery has been something that I've been watching evolve for some time. The work is speaking about the Black Summer bushfires in Australia last year.

KAIt was the end of 2019, when I started watching the news. I was not in Australia, but from the other side of the world I could see the bushfires and distressed animals who were running for their lives. It was very disturbing to see koalas running for their lives.

I told my friend Asad Buda, 'Let's consider epic and fictitious animals like the phoenix or dragons to talk about extinction.' And then he said, 'How about we think about the animals that are now on the verge of extinction? Let's talk about koalas. Let's talk about kangaroos.' And so we worked for two months to come up with a text called Sermon on the Mount. The work itself is an illustration of that story, and based on the Kalila and Dimna.

For me, Australian native animals were always missing from my childhood stories. My grandfather used to sing stories from the Kalila and Dimna, which is a book that was written almost 2,000 years ago in India and loosely translates to 'All the animals of the world'. But the book itself doesn't have Australian animals in it.

We wanted to add Australian animals to the work. For a person like me living in Australia, my world should have Australian animals in it, too. The title originated because I went to a Christian school in Pakistan and one of the first or significant lessons from the Bible in our school was the Sermon on the Mount, where Jesus goes to the mountain and then talks about hope for the future.

In the Sermon on the Mount, a koala is giving a speech about hopelessness and the modern melancholy of how animals in Australia are on the verge of extinction. The Government talks about helping war-torn countries like Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan, but what about addressing climate change and the corporations who have caused this? Why do we not see these animals as refugees?

No comments:

Post a Comment