Source: BrooklynRail

Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities

Born in Lahore in 1969, Shahzia Sikander spent part of her teenage years in Africa. In 1989, at the age of 20, she visited London, where she discovered the mystical work of Anselm Kiefer. Returning to Pakistan, she enrolled at the National College of Arts, a bastion of creative freedom under the military dictatorship of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Many of the artists teaching at the NCA were unabashed modernists; others were looking for ways to combine modernism with the tradition of Mughal miniature painting. Sikander chose to study with Bashir Ahmad, who was devoted to preserving its classical language.

Arriving in the United States in 1993, Sikander studied at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). In 1997, she was included in the Whitney Biennial along with other artists from outside the New York mainstream such as Gabriel Orozco, Cecilia Vicuña, Kerry James Marshall, and Kara Walker. In 1998, Bard’s Center for Curatorial Studies showed her together with Byron Kim and Yinka Shonibare. In these years, the discovery of artists from outside the United States and Europe went hand-in-hand with the discovery of artists of color from within the United States. Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities, curated by Jan Howard for the RISD Museum and currently on view at the Morgan Library, takes us back to the Big Bang of global contemporary art.

The exhibition (beautifully installed at the Morgan by Isabelle Dervaux) is divided into four chapters. First, we encounter Sikander’s early work, where she used the painstaking technique of Mughal miniature painting to evoke the condition of modern Pakistani women, living cloistered existences under the Hudood Ordinances imposed in 1979. Set within modern versions of Mughal painting’s axonometric architecture, Sikander’s haunting narratives recall the work of Mexican surrealist Remedios Varo.

The second chapter of the exhibition surveys Sikander’s two years at RISD (1993–95), where she experimented with radically different imagery: black, flowing ink drawings of women’s bodies, exaggerating breasts and thighs and replacing hands and feet with looping tendrils, like roots turned back upon themselves. These images of what Jan Howard calls “female interiority” were inspired by artists like Eva Hesse, Ana Mendieta, and Mona Hatoum; by feminist theorists like Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray, Hélène Cixous, and bell hooks; and by feminist poets from Pakistan like Fahmida Riaz and Kishwar Naheed. Sikander also used flowing lines of white ink to surround her figures with veils and burqas, sometimes suggesting cages and sometimes protective carapaces. Sikander’s radical reinvention of her artistic identity was assisted by friendships formed at RISD with instructors like the African American painter Donnamaria Bruton and with fellow students like Kara Walker and Julie Mehretu. The artistic exchanges between Sikander, Walker, and Mehretu helped write the agenda for subsequent contemporary art, much as the interaction between Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns determined the key issues for American art of the 1960s.

After RISD, Sikander spent two years at the Glassell School of Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Stopping in a series of southern cities during her drive from Providence to Houston, Sikander came to see American slavery as a consequence of British imperialism, different from but intimately related to the colonial history of South Asia. Mehretu arrived in Houston a year later. Both of them were deeply involved with the Project Row Houses founded in 1994 by Rick Lowe and a group of local artists, who created a new kind of “social sculpture” by buying and restoring a group of small shotgun houses, some of which became housing for single mothers completing their educations, while others provided spaces for artists to make installations. The project reinforced Sikander’s bonds with other participants such as Mehretu and Fred Wilson, and she also became close to artists like Carrie Mae Weems and Mel Chin, who were in Houston at the time.

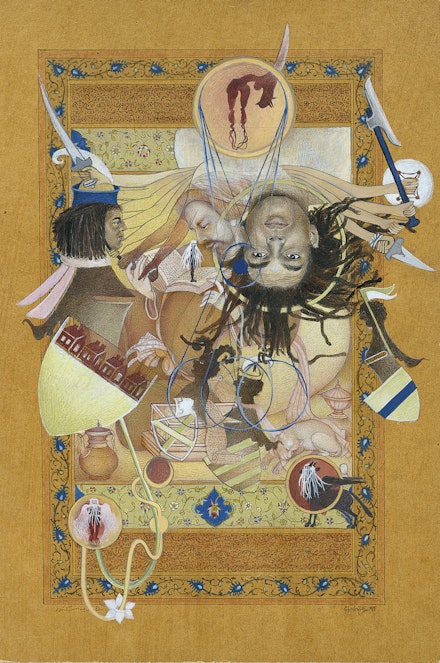

In her last months at RISD, Sikander experimented with adding fluid, formless figures to her earlier miniatures, and in Houston this process of overpainting became central to her work. In a recent interview with Rafia Zakaria, she notes that “I was violating my own work in an attempt to unlearn and learn simultaneously.” The formless figures were accompanied by new personae, some borrowed from Hindu miniatures, others from contemporary visual culture. For instance, in Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings, completed in 1997, she began with a 1989 painting based on a 16th-century miniature of a man reading, and added a variety of new images: meticulously drawn portraits of Rick Lowe (full-face and in profile), heraldic blazons (one showing the Row Houses), circles containing versions of her self-rooted figure, and disembodied arms clutching knives and hatchets, evoking the Hindu goddess Durga. Around this time, she also broke out of the formal constraints of the miniature, creating mural-scale montages with her new repertory of figures painted directly on the wall or onto hanging strips of translucent paper. (A mural montage in this style forms the centerpiece of the Morgan installation.)

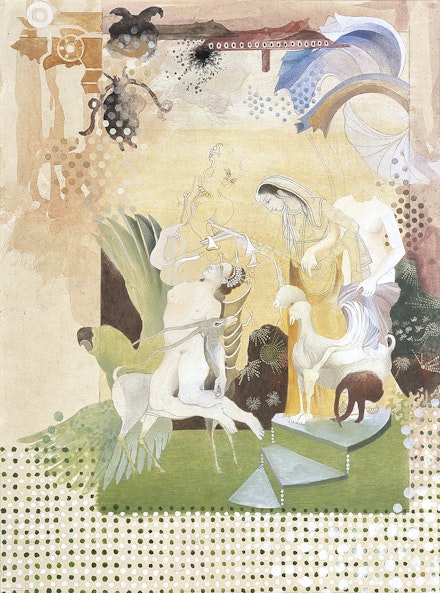

In 1997 Sikander moved to New York. It meant separating from the supportive group of artists she had found in Houston, but she rapidly acquired a new community. In the RISD catalog, Julie Mehretu recalls Sikander’s exhibition openings as bringing together groups that were usually invisible in the art world and that rarely mixed with one another: Pakistani with Indian, East African with African American, trans with cis. Sikander’s major iconographic innovation of these years was an image of two women joined in a weightless embrace: an 11th-century Devata figure in the Hindu tradition of erotic temple sculpture, with her bent knee perched atop the shoulder of the central figure from Agnolo Bronzino’s Allegory of Venus and Cupid (ca. 1545). Venus steadies Devata by grasping her extended foot and reaches upward to tug provocatively at her necklace. The pair is represented at the Morgan by a 2001 drawing, Intimacy, and a sculpture, Promiscuous Intimacies (2020), more sensual than its painted prototypes.

However, the effective conclusion of the exhibition is the 2003 video SpiNN (like the television network CNN but spinning). This announces Sikander’s venture into the world of animation, a frequent element of her more recent work. The setting of the video shows the throne room of Shah Jahan, a 17th-century emperor, as depicted in a painting by the Mughal master Bichitr. But the emperor and his courtiers have vanished, and the space is invaded by a crowd of nude gopis (cowherding girls), who are then transformed into a swarm of bat-like black creatures. (These prove, on close inspection, to be remnants of their black hair, pulled up into topknots.) With Maligned Monsters and SpiNN, Sikander moves into the realm of magic realism: a visual equivalent to the fiction of Rabih Alameddine, Salman Rushdie, Qurratulain Hyder, and Gabriel GarcíaMárquez.

Sikander’s extraordinary impact on American art becomes more comprehensible if we revisit the early 1990s, just before her arrival in the United States. The 1993 Whitney Biennial thrust identity politics onto the center stage of contemporary art. At the time, it was widely denounced as excessively political; in hindsight, it seems prescient. Homi Bhabha’s catalog essay, “Beyond the Pale: Art in the Age of Multicultural Translation,” provided a manifesto for diasporic consciousness. Bhabha called for a “new internationalism” emerging from “the history of postcolonial migration.” He insisted on “the need to think beyond narratives of origin.” As he saw it, the new avant-garde would focus on “‘in-between’ spaces” and the “interstices” between cultures. In the mid-1990s, Sikander, Mehretu, and Walker began to make art that did exactly that.

Even in 1993, however, Bhabha anticipated that the relationships between communities with “shared histories of deprivation and discrimination” might nonetheless be “profoundly antagonistic [and] conflictual.” There was no guarantee that the utopian community of diasporic artists in New York could provide a model for the larger world. Indeed, the decades since 1993 have demonstrated that artistic heritage can too easily be co-opted into the service of right-wing nationalism.

Sikander’s work, from 1993 onward, ferociously defies co-optation. She subverts heritage as rapidly as she invokes it. Layering images from multiple sources and in multiple visual languages, she operates in the cultural interstices described by Bhabha. It should be noted that an American audience is at risk of seeing Sikander as working primarily in the space between South Asian and Euro-American culture. Certainly, the encounter between these cultures is evoked by her repeated pairing of Devata and Venus.

What is more fundamental to her work, however, are the tensions within South Asian culture. From the foundation of the Mughal Empire in the 16th century until the subcontinent’s violent partition in 1947, South Asian culture was an indissoluble mixture of Hindu and Islamic elements. Painters and writers drew freely on multiple traditions. After 1947, however, artists and writers in the new state of Pakistan came under increasing pressure to invent a purely Islamic heritage, excluding the Hindu elements of their culture. Conversely, the right-wing government of India has in recent years attempted to eliminate the Islamic elements of the country’s history and culture. Sikander’s work unwaveringly resists this pressure for cultural uniformity.

This resistance is visible in Sikander’s early painting Perilous Order, on view at the Morgan, and in an important series of sequels. Perilous Order began in 1989 as what seemed to be a study in the manner of Mughal portraiture, showing a bearded king or prince in profile, framed within an oval, with a rectangular border filled with elegant, interlacing tendrils. In a recent interview, Sikander explained that it was in fact a portrait of a gay friend, intended as a comment “on homosexuality and its precarious existence within the Punjabi culture of Lahore.” In 1994–97 she reworked the image. First, she added a larger decorative border, covered with swirling patterns. Then she inserted her self-rooted figure, its breasts surrounding the man’s face and its thighs occupying his torso. Finally, she added several nude female figures, one emerging from the inner oval of the portrait, the other three ascending and descending from its rectangular frame.

In a 2001 conversation with Vishakha Desai, Sikander explained that Bashir Ahmad, her guide to the tradition of the Mughal miniature, also introduced her to the non-Mughal traditions of South Asian art. In another discussion, with Fereshteh Daftari, Sikander noted that the female figures in Perilous Order were “plucked from a Basohli painting, an early 18th-century illustration of the Bhagavata Purana, showing maidens whose clothes Krishna has stolen.” Indeed, M.S. Randhawa’s Basohli Painting (Calcutta, 1959) reveals that the nude figures in Perilous Order are exact reproductions of four gopis in an 18th-century miniature, who have disrobed so that they can bathe in a secluded pool.

The gopis from the Basohli miniature are a recurrent presence in Sikander’s work. They appear in her 1995 painting Apparatus of Power, in the 2001 painting Gopi Crisis, and in the early stages of the 2003 animation SpiNN. The narrative of Krishna Stealing the Clothes of Cowherdesses casts some light on the recurring “gopi crisis.” According to the Bhagavata Purana, the god Krishna stole the clothes of the bathing gopis and hid in a nearby tree. After an initial moment of panic, the gopis recognized Krishna and bowed their heads in prayer. Mocking their modesty, Krishna insisted that they climb naked from the water to reclaim their clothes. As Randhawa, the editor of the Basohli album, explains, “When the soul goes forth into the darkness of the unconditioned to meet the Supreme Being to yield herself to Him, she goes in all her nakedness.”

What, then, do the gopis mean in Sikander’s work? In Perilous Order, they seem at first glance to be in orbit around the princely figure. Or are the dark “root” figure and the pale encroaching nudes meant to challenge his masculine authority? (And what does this say about the precariousness of homosexual desire within Punjabi society?) In Gopi Crisis, dark formless figures surround a milling crowd of nudes. What exactly is the crisis? Is it the terror of the gopis, discovered in their nakedness? Or is it their refusal to be intimidated? In SpiNN, the symbolism seems more straightforward: the gopis occupy the seat of power. But then they dissolve into their hairdos and fly away.

There are no simple answers in Sikander’s work. But there is an urgent invitation to walk through the looking glass into a series of different worlds, foreign yet uncannily familiar, where the partitions of other continents reveal the fault lines of our own.

No comments:

Post a Comment